Modal Auxiliary Verbs

What is a modal auxiliary verb?

A modal auxiliary verb, often simply called a modal verb or even just a modal, is used to change the meaning of other verbs (commonly known as main verbs) by expressing modality—that is, asserting (or denying) possibility, likelihood, ability, permission, obligation, or future intention.

Modal verbs are defined by their inability to conjugate for tense and the third person singular (i.e., they do not take an “-s” at the end when he, she, or it is the subject), and they cannot form infinitives, past participles, or present participles. All modal auxiliary verbs are followed by a main verb in its base form (the infinitive without to); they can never be followed by other modal verbs, lone auxiliary verbs, or nouns.

As with the primary auxiliary verbs, modal verbs can be used with not to create negative sentences, and they can all invert with the subject to create interrogative sentences.

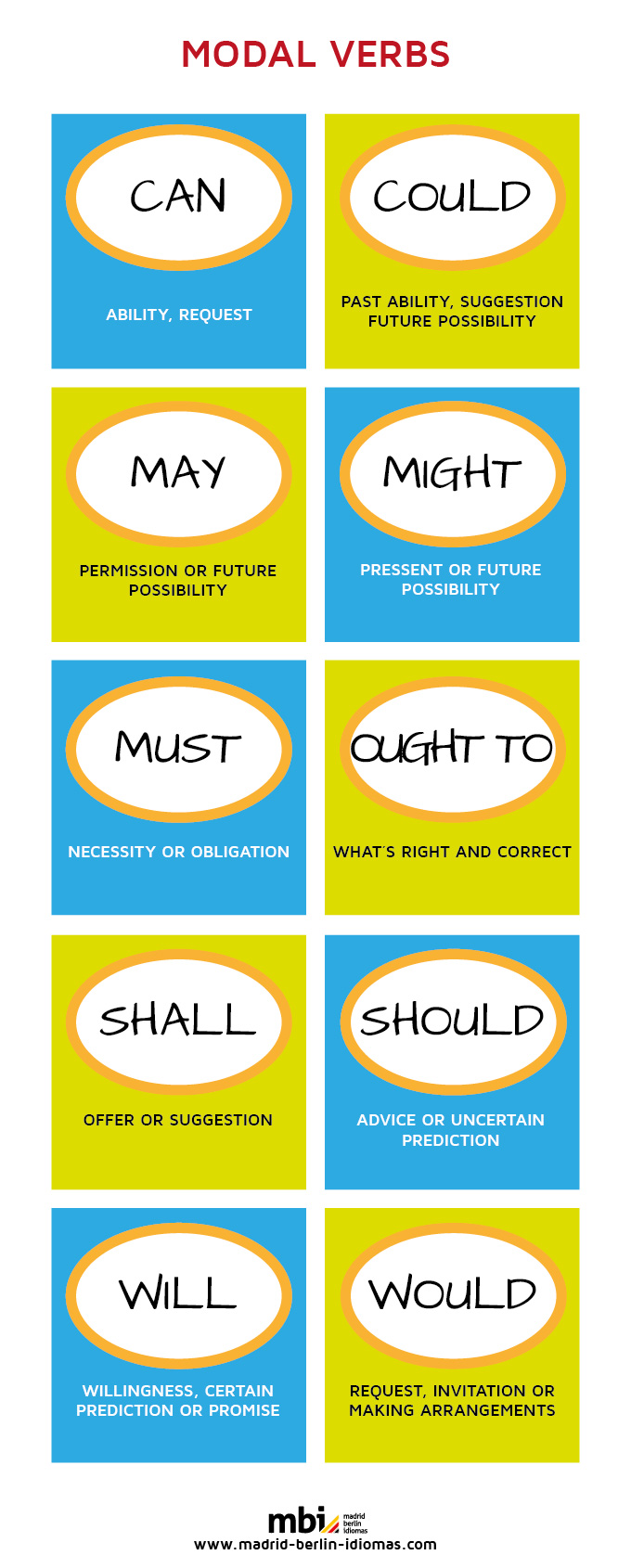

The Modal Verbs

There are nine “true” modal auxiliary verbs: will, shall, would, should, can, could, may, might, and must. The verbs dare, need, used to, and ought to can also be used in the same way as modal verbs, but they do not share all the same characteristics; for this reason, they are referred to as semi-modal auxiliary verbs, which are discussed in a separate section.

We’ll give a brief overview of each modal verb below, but you can continue on to their individual sections to learn more about when and how they are used.

Will

As a modal auxiliary verb, will is particularly versatile, having several different functions and meanings. It is used to form future tenses, to express willingness or ability, to make requests or offers, to complete conditional sentences, to express likelihood in the immediate present, or to issue commands.

Shall

The modal auxiliary verb shall is used in many of the same ways as will: to form future tenses, to make requests or offers, to complete conditional sentences, or to issue maxims or commands. Although will is generally preferred in modern English, using shall adds an additional degree of politeness or formality to the sentence that will sometimes lacks.

Generally, shall is only used when I or we is the subject, though this is not a strict rule (and does not apply at all when issuing commands, as we’ll see).

Would

The modal auxiliary verb would has a variety of functions and uses. It is used in place of will for things that happened or began in the past, and, like shall, it is sometimes used in place of will to create more formal or polite sentences. It is also used to express requests and preferences, to describe hypothetical situations, and to politely offer or ask for advice or an opinion.

Should

The modal verb should is used to politely express obligations or duties; to ask for or issue advice, suggestions, and recommendations; to describe an expectation; to create conditional sentences; and to express surprise. There are also a number of uses that occur in British English but are not common in American English.

Can

As a modal auxiliary verb, can is most often used to express a person or thing’s ability to do something. It is also used to express or ask for permission to do something, to describe the possibility that something can happen, and to issue requests and offers.

Could

The modal verb could is most often used as a past-tense version of can, indicating what someone or something was able to do in the past; it can also be used instead of can as a more polite way of making a request or asking for permission. Could is also used to express a slight or uncertain possibility, as well as for making a suggestion or offer.

May

The modal verb may is used to request, grant, or describe permission; to politely offer to do something for someone; to express the possibility of something happening or occurring; or to express a wish or desire that something will be the case in the future. We can also use may as a rhetorical device to express or introduce an opinion or sentiment about something.

Might

The modal verb might is most often used to express an unlikely or uncertain possibility. Might also acts as a very formal and polite way to ask for permission, and it is used as the past-tense form of may when asking permission in reported speech. It can also be used to suggest an action, or to introduce two differing possibilities.

Must

The modal verb must is most often used to express necessity—i.e., that something has to happen or be the case. We also use this sense of the word to indicate a strong intention to do something in the future, to emphasize something positive that you believe someone should do, and to rhetorically introduce or emphasize an opinion or sentiment. In addition to indicating necessity, must can be used to indicate that something is certain or very likely to happen or be true.

Using Modal Verbs

Modal auxiliary verbs are used to uniquely shift the meaning of the main verb they modify, expressing things such as possibility, likelihood, ability, permission, obligation, or intention. As we will see, how and when we use modal verbs greatly affects the meaning of our writing and speech.

Subtleties in meaning

Modal verbs attach differing shades of meaning to the main verbs they modify. It is often the case that this difference in meaning is or seems to be very slight. To get a better sense of these differences in meaning, let’s look at two sets of examples that use each of the modal verbs we discussed above in the same sentence, accompanied by a brief explanation of the unique meaning each one creates.

- “I will go to college in the fall.” (It is decided that I am going to attend college in the fall.)

- “I shall go to college in the fall.” (A more formal way of saying “I will go to college in the fall,” possibly emphasizing one’s determination to do so.)

- “I would go to college in the fall.” (I was planning to attend college in the fall (but something not stated is preventing or dissuading me from doing so).)

- “I should go to college in the fall.” (It is correct, proper, or right that I attend college in the fall.)

- “I can go to college in the fall.” (I am able to attend college in the fall.)

- “I could go to college in the fall.” (I have the ability to attend college in the fall, but it is not decided.)

- “I may go to college in the fall.” (I will possibly attend college in the fall, but it is not decided.)

- “I might go to college in the fall.” (I will possibly attend college in the fall, but it is not decided.)

- “I must go to college in the fall.” (I have to attend college in the fall, but it is not decided.)

- “Will we spend the summer in Florida?” (Is it the future plan that we are going to spend the summer in Florida?)

- “Shall we spend the summer in Florida?” (A more formal way of asking “Will we spend the summer in Florida?”)

- “Would we spend the summer in Florida?” (Has the plan been made that we spend the summer in Florida?)

- “Should we spend the summer in Florida?” (Is it correct or preferable that we spend the summer in Florida?)

- “Can we spend the summer in Florida?” (Can we have permission to spend the summer in Florida? Or: Are we able to spend the summer in Florida?)

- “Could we spend the summer in Florida?” (Slightly more polite way of asking for permission to spend the summer in Florida.)

- “May we spend the summer in Florida?” (More formal or polite way of asking for permission to spend the summer in Florida.)

- “Might we spend the summer in Florida?” (Overly formal way of asking for permission to spend the summer in Florida.)

- “Must we spend the summer in Florida?” (Very formal way of asking if it is necessary or required that we spend the summer in Florida.)

Omitting main verbs

A modal verb must always be used with a main verb—they cannot stand completely on their own.

However, it is possible to use a modal verb on its own by omitting the main verb, so long as it is implied by the context in or around the sentence in which the modal is used. This can occur when a sentence is in response to another one, or when the clause with the modal verb occurs later in a sentence in which the main verb was already stated. For example:

- Speaker A: “I’m thinking about taking up scuba diving.”

- Speaker B: “I think you should!” (The verb taking up is omitted in the second sentence because it is implied by the first.)

- “I’d like to switch my major to mathematics, but I’m not sure I can.” (The verb switch is omitted in the final clause because it appears earlier in the same sentence.)

Using adverbs

Generally speaking, we use adverbs after a modal verb and either before or after the main verb in a clause. Sometimes putting an adverb before a modal is not incorrect, but it will sound better if placed after it. For example:

- “You must only read this chapter.” (correct)

- “You only must read this chapter.” (incorrect)

- “You could easily win the race.” (correct)

- “You could win the race easily.” (correct)

- “You easily could win the race.” (correct but not preferable)

However, this is not a strict rule, and certain adverbs are able to go before the modal verb without an issue. For example:

- “You really should see the new movie.” (correct)

- “You should really see the new movie.” (correct)

- “I definitely will try to make it to the party.” (correct)

- “I will definitely try to make it to the party.” (correct)

When a modal verb is made negative, though, it is sometimes the case that an adverb must go before the modal verb. For example:

- “I definitely can’t go out tonight.” (correct)

- “I can’t definitely go out tonight.” (incorrect)

- “He absolutely must not travel” (correct)

- “He must not absolutely travel” (incorrect)

Unfortunately, there is no rule that will explain exactly when one can or cannot use an adverb before a modal verb—we just have to learn the correct usage by seeing how they are used in day-to-day speech and writing.

Common errors

Mixing modal verbs

Remember, a modal verb is only used before a main verb, or sometimes before be or have when they are used to create a verb tense. We do not use a modal verb before auxiliary do, or in front of other modal verbs. For example:

- “We might move to Spain.” (correct—indicates future possibility)

- “We might be moving to Spain.” (correct—indicates future possibility using the present continuous tense)

- “Can you go?” (correct)

- “Do you can go?” (incorrect)

- “I must finish this before lunch.” (correct—indicates that it is necessary)

- “I will finish this before lunch.” (correct—indicates a future action)

- “I must will finish this before lunch.” (incorrect)

Conjugating the third-person singular

When main verbs function on their own, we conjugate them to reflect the third-person singular (usually accomplished by adding “-s” to the end of the verb).

However, we do not conjugate modal verbs in this way, nor do we conjugate a main verb when it is being used with a modal.

For example:

- “He swims” (present simple tense)

- “He can swim” (correct—indicates ability)

- “He cans swim” (incorrect)

- “He can swims” (incorrect)

Conjugating past tense

Similarly, we cannot use modal verbs with main verbs that are in a past-tense form; the verb that follows a modal must always be in its base form (the infinitive without the word to). Instead, we either use certain modal verbs that have past-tense meanings of their own, or auxiliary have to create a construction that has a specific past-tense meaning.

For example:

- “I guessed what her response would be.” (past simple tense)

- “I could guess what her response would be.” (correct—indicates past ability)

- “I can guessed what her response would be.” (incorrect)

- “I could have guessed what her response would be.” (correct—indicates potential past ability)

- “I could guessed what her response would be.” (incorrect)

- “I tried” (past simple tense)

- “I should have tried” (correct—indicates a correct or proper past action)

- “I should try” (correct, but indicates a correct or proper future action)

- “I should tried” (incorrect)

Following modal verbs with infinitives

As we saw above, all modal auxiliary verbs must be followed by the base form of the main verb. Just as we cannot use a modal verb with a main verb in its past-tense form, we also cannot use a modal verb with an infinitive:

- “She could speak five languages.” (correct—indicates past ability)

- “She could to speak five languages.” (incorrect)

- “I must see the boss.” (correct—indicates necessity)

“I must to see the boss.” (incorrect)

Modal Auxiliary Verbs – Will

Definition

As a modal auxiliary verb, will is particularly versatile, having several different functions and meanings. It is used

- To form future tenses.

- To express willingness or ability.

- To make requests or offers.

- To complete conditional sentences.

- To express likelihood in the immediate present.

- To issue commands.

- Creating the future tense

One of will’s most common uses as a modal verb is to talk about things that are certain, very likely, or planned to happen in the future. In this way, it is used to create an approximation of the future simple tense and the future continuous tense. For example:

- “I will turn 40 tomorrow.” (future simple tense)

- “She will be singing at the concert as well.” (future continuous tense)

Will can also used to make the future perfect tense and the future perfect continuous tense. These tenses both describe a scenario that began in the past and will either finish in or continue into the future. For example:

- “It’s hard to believe that by next month we will have been married for 10 years.” (future perfect tense)

- “By the time I get there, she’ll have been waiting for over an hour.” (future perfect continuous tense)

If we want to make any of the future tenses negative, we use not between will and the main verb or the next occurring auxiliary verb. We often contract will and not into won’t. For example:

- “I won’t be seeing the movie with you tonight.”

- “At this pace, she won’t finish in first place.”

If we want to make a question (an interrogative sentence), we invert will with the subject, as in:

- “What will they do with the money?”

- “Won’t you be coming with us?”

- Ability and willingness

We also sometimes use will to express or inquire about a person or thing’s ability or willingness to do something. It is very similar to the future tense, but is used for more immediate actions. For example:

- “You wash the dishes; I’ll take out the trash.”

- “This darn washing machine won’t turn”

- “Won’t Mary come out of her room?”

- Requests and offers

We often create interrogative sentences using will to make requests or polite offers. They are usually addressed to someone in the second person, as in:

- “Will you walk the dog, Jim?”

- “Will you have a cup of tea, Sam?”

However, we can use subjects in the first and third person as well. For instance:

- “Will Jonathan bring his truck around here tomorrow?”

- “Will your friend join us for some lunch?”

- Conditional sentences

In present-tense conditional sentences formed using if, we often use will to express an expected hypothetical outcome. This is known as the first conditional. For example:

- “If I see him, I will tell him the news.”

- “I won’t have to say goodbye if I don’t go to the airport.”

- Likelihood and certainty

In addition to expressing actions or intentions of the future, we can also use will to express the likelihood or certainty that something is the case in the immediate present. For instance:

- (in response to the phone ringing) “That will be Jane—I’m expecting her call.”

- Speaker A: “Who is that with Jeff?”

- Speaker B: “That’ll be his new husband. They were just married in May.”

- Commands

Finally, we can use will to issue commands, orders, or maxims. These have an added forcefulness in comparison to imperative sentences, as they express a certainty that the command will be obeyed. For example:

- “You will finish your homework this instant!”

- “This house will not be used as a hotel for your friends, do you understand me?”

Substituting Modal Verbs

In many cases, modal auxiliary verbs can be used in place of others to create slightly different meanings. For example, we can use the word shall in place of will in to express polite invitations. Similarly, would can also be substituted for will in requests to make them more polite.

Explore the section on Substituting Modal Verbs to see how and when other modal auxiliary verbs overlap.

Modal Auxiliary Verbs – Would

Definition

The modal auxiliary verb would has a variety of functions and uses. It is used in place of will for things that happened or began in the past, and, like shall, it is sometimes used in place of will to create more formal or polite sentences. It is also used to express requests and preferences, to describe hypothetical situations, and to politely offer or ask for advice or an opinion.

1.Creating the future tense in the past

When a sentence expresses a future possibility, expectation, intention, or inevitability that began in the past, we use would instead of will. For example:

- “I thought he would be here by now.”

- “She knew they wouldn’t make it to the show in time.”

- “I thought John would be mowing lawn by this point.”

- Past ability and willingness

We also use would for certain expressions of a person or thing’s ability or willingness to do something in the past, though they are usually negative. For example:

- “This darn washing machine wouldn’t turn on this morning.”

- “Mary wouldn’t come out of her room all weekend.”

- Likelihood and certainty

Like we saw with will, we can also use would to express the likelihood or certainty that something was the case in the immediate past. For instance:

- Speaker A: “There was a man here just now asking about renting the spare room.”

- Speaker B: “That would be He just moved here from Iowa.”

- Polite requests

We can use would in the same way as will to form requests, except that would adds a level of politeness to the question, as in:

- “Would you please take out the garbage for me?”

- “Would John mind helping me clean out the garage?”

5.Expressing desires

We use would with the main verb like to express or inquire about a person’s desire to do something. (We can also use the main verb care for more formal or polite sentences.) For example:

- “I would like to go to the movies later.”

- “Where would you like to go for your birthday?”

- “I would not care to live in a hot climate.”

- “Would you care to have dinner with me later?”

We can use this same construction to express or ask about a desire to have something. If we are using like as the main verb, it can simply be followed by a noun or noun phrase; if we are using care, it must be followed by the preposition for, as in:

- “Would you like a cup of tea?”

- “He would like the steak, and I will have the lobster.”

- “Ask your friends if they would care for some snacks.”

6.Would that

Would can also be used to introduce a that clause to indicate some hypothetical or hopeful situation that one wishes were true. For example:

- “Would that we lived near the sea.”

- Speaker A: “Life would be so much easier if we won the lottery.”

- Speaker B: “Would that it were so!”

This is an example of the subjunctive mood, which is used to express hypotheticals and desires. While we still use would in the subjunctive mood to express preference or create conditional sentences (like Speaker A’s sentence above), today the would that construction is generally only found in very formal, literary, old-fashioned, or highly stylized speech or writing.

- Preference

We use would with the adverbs rather and sooner to express or inquire about a person’s preference for something. For instance:

- “There are a lot of fancy meals on the menu, but I would rather have a hamburger.”

- “They would sooner go bankrupt than sell the family home.”

- “Would you rather go biking or go for a hike?”

- Conditional sentences

Conditional sentences in the past tense are called second conditionals. Unlike the first conditional, we use the second conditional to talk about things that cannot or are unlikely to happen.

To create the second conditional, we use the past simple tense after the if clause, followed by would + the bare infinitive for the result of the condition. For example:

- “If I went to London, I would visit Trafalgar Square.”

- “I would buy a yacht if I ever won the lottery.”

- Hypothetical situations

We can also use would to discuss hypothetical or possible situations that we can imagine happening, but that aren’t dependent on a conditional if clause.

For example:

- “They would be an amazing band to see in concert!”

- “Don’t worry about not getting in—it wouldn’t have been a very interesting class, anyway.”

- “She would join your study group, but she doesn’t have any free time after school.”

- “I normally wouldn’t mind, except that today is my birthday!”

- Polite opinions

We can use would with opinion verbs (such as think or expect) to dampen the forcefulness of an assertion, making it sound more formal and polite:

- “I would expect that the board of directors will be pleased with this offer.”

- “One would have thought that the situation would be improved by now.”

We can also ask for someone else’s opinion with would by pairing it with a question word in an interrogative sentence, as in:

- “What would you suggest we do instead?”

- “Where would be a good place to travel this summer?”

- Asking the reason why

When we use the question word why, we often follow it with would to ask the reason something happened or is true. For instance:

- “Why would my brother lie to me?”

- “Why would they expect you to know that?”

If we use I or we as the subject of the question, it is often used rhetorically to suggest that a question or accusation is groundless or false, as in:

- “Why would I try to hide anything from you?”

- “Why would we give up now, when we’ve come so close to succeeding?”

- Polite advice

We can use would in the first person to politely offer advice about something. (It is common to add the phrase “if I were you” at the end, thus creating a conditional sentence.) For example:

- “I would apologize to the boss if I were you.”

- “I would talk to her tonight; there’s no point in waiting until tomorrow.”

We can also use would in the second and third person to offer advice, usually in the construction “you would be wise/smart to do something,” as in:

- “I think you would be wise to be more careful with your money.”

- “Recent graduates would be smart to set up a savings account as early as possible.”

Substituting Modal Verbs

In many cases, modal auxiliary verbs can be replaced with others to create slightly different meanings.

For example, in addition to using would to form the second conditional (which we use to describe something we would definitely do), we can also use could for what we would be able to do, as well as might for what it is possible (but unlikely) we would do.

For example:

- “If I won the lottery, I could buy a new house.”

- “If I were older, I might stay up all night long.”

In British English, should is often used in place of would in many constructions to add politeness or formality. For instance:

- “I should apologize to the boss if I were you.” (polite advice)

- “I should like a poached egg for breakfast.” (desire)

Modal Auxiliary Verbs – Shall

Definition

The modal auxiliary verb shall is used in many of the same ways as will: to form future tenses, to make requests or offers, to complete conditional sentences, or to issue maxims or commands. Although will is generally preferred in modern English (especially American English), using shall adds an additional degree of politeness or formality to the sentence that will sometimes lacks.

Traditionally, shall is only used to form the future simple and future continuous tenses when I or we is the subject, though this is not a strict rule (and does not apply at all when issuing commands, as we’ll see).

Creating the future tense

The future tenses are most often formed using will or be going to.

We can also use shall to add formality or politeness to these constructions, especially the future simple tense and the future continuous tense. For example:

- “I shall call from the airport.” (future simple tense)

- “We shall be staying in private accommodation.”

- “We shall not be in attendance this afternoon.”

- “I shan’t* be participating in these discussions.”

(*Contracting shall and not into shan’t, while not incorrect, sounds overly formal and stuffy in modern speech and writing; for the most part, it is not used anymore.)

It is also possible, though far less common, to use shall in the future perfect and future perfect continuous tenses as well:

- “As of next week, I shall have worked here for 50 years.”

- “By the time the opera begins, we shall have been waiting for over an hour.”

Offers, suggestions, and advice

When we create interrogative sentences using shall and without question words, it is usually to make polite offers, invitations, or suggestions, as in:

- “Shall we walk along the beach?”

- “Shall I wash the dishes?”

When we form an interrogative sentence with a question word (who, what, where, when, or how), shall is used to politely seek the advice or opinion of the listener about a future decision, as in:

- “What shall I do with this spare part?”

- “Where shall we begin?”

- “Who shall I invite to the meal?”

Conditional sentences

Like will, we can use shall in conditional sentences using if to express a likely hypothetical outcome. This is known as the first conditional. For example:

- “If my flight is delayed, I shall not have time to make my connection.”

- “I shall contact the post office if my package has not arrived by tomorrow.”

Formal commands, maxims, and statements of obligation

While will is often used to form commands, we use shall when issuing more formal directives or maxims, as might be seen in public notices or in a formal situation, or to express a reprimand or obligation in a formal way. When used in this way, shall no longer has to be used solely with I or we as the subject. For example:

- “This establishment shall not be held liable for lost or stolen property.”

- “Students shall remain silent throughout the exam.”

- “The new law dictates that no citizen shall be out on the streets after 11 PM.”

- “You shall cease this foolishness at once!”

- “They shall be punished for their transgression.”

Substituting Modal Verbs

In many cases, modal auxiliary verbs can be used in place of others to create slightly different meanings. For example, we can use the word should in place of shall when issuing a command that is not mandatory, but rather is a guideline or recommendation. If, however, we want to express that the command or maxim is an absolute requirement, we can use must instead of shall in this context.

Explore the section Substituting Modal Verbs to see how and when other modal auxiliary verbs overlap.

Modal Auxiliary Verbs – Should

Definition

The modal verb should is used to

- politely express obligations or duties;

- to ask for or issue advice, suggestions, and recommendations;

- to describe an expectation;

- to create conditional sentences; and

- to express surprise.

There are also a number of uses that occur in British English that are not common in American English.

- Polite obligations

Should is used in the same construction as other modal verbs (such as will, shall, and must) to express an obligation or duty.

However, whereas must or will (and even shall) make the sentence into a strict command, which might appear to be too forceful and could be seen as offensive, should is used to create a more polite form that is more like a guideline than a rule. For example:

- “Guests should vacate their hotel rooms by 10 AM on the morning of their departure.”

- “I think she should pay for half the meal.”

- “You shouldn’t play loud music in your room at night.”

- “I think healthcare should be free for everyone.”

- “She should not be here; it’s for employees only.”

Asking the reason why in polite obligations

We can follow the question word why with should to ask the reason for a certain obligation or duty. For instance:

- “Why should I have to pay for my brother?”

- “Why shouldn’t we be allowed to talk during class?”

- Advice and recommendations

Should can also be used to issue advice or recommendations in much the same way. For instance:

- “You should get a good map of London before you go there.” (recommendation)

- “You shouldn’t eat so much junk food—it’s not good for you.” (advice)

We can also use should in interrogative sentences to ask for someone’s advice, opinion, or suggestion, as in:

- “What should I see while I’m in New York?”

- “Should she tell her boss about the missing equipment?”

- “Is there anything we should be concerned about?”

- Expectations

Should can be used in affirmative (non-negative) sentences to express an expected outcome, especially when it is followed by the verb be. For example:

- “She should be here by now.”

- “They should be arriving at any minute.”

- “I think this book should be”

We can also follow should with other verbs to express expectation, but this is less common. For instance:

- “They should find this report useful.”

- “We should see the results shortly.”

If we use the negative of should (should not or shouldn’t), it implies a mistake or error, especially when we use it with a future time expression. For example:

- “She shouldn’t be here yet.”

- “He shouldn’t be arriving for another hour.”

We normally do not use should not to refer to expected future actions like we do in the affirmative; it generally refers to something that just happened (in the present or immediate past).

Should vs. be supposed to vs. be meant to

In many instances, should can be replaced by be supposed to or be meant to with little to no change in meaning. For instance, we can use be supposed to or be meant to in place of should for something that is expected or required to happen.

For example:

- “He should be here at 10 AM.”

- “He is meant to be here at 10 AM.”

- “He is supposed to be here at 10 AM.”

We can also use these three variations interchangeably when asking the reason why something is the case. For instance:

- “Why should I have to pay for my brother?”

- “Why am I meant to pay for my brother?”

- “Why am I supposed to pay for my brother?”

However, when we are expressing an obligation or duty, we can only replace should with be supposed to or be meant to when it is in the negative. For instance:

- “You shouldn’t play loud music in your room at night.”

- “You aren’t meant to play loud music in your room at night.”

- “You aren’t supposed to play loud music in your room at night.”

In affirmative sentences in which should expresses an obligation or duty (as opposed to an expectation), these verbs are not interchangeable. For instance:

- “I think she should pay for half the meal.” (obligation)

- “I think she is supposed to pay for half the meal.” (expectation)

- “I think she is meant to pay for half the meal.” (expectation)

Be supposed to and be meant to are also used to express general beliefs, which is not a way we can use the modal verb should.

For example:

- “He is supposed to be one of the best lawyers in town.” (general belief)

- “He is meant to be one of the best lawyers in town.” (general belief)

- “He should be one of the best lawyers in town.” (obligation)

We can see how the meaning changes significantly when should is used instead.

- Conditional Sentences

Should can be used in conditional sentences to express an outcome to a possible or hypothetical conditional situation.

Sometimes we use should alongside if to create the conditional clause, as in:

- “If anyone should ask, I will be at the bar.”

- “If your father should call, tell him I will speak to him later.”

We can also use should on its own to set up this condition, in which case we invert it with the subject. For example:

- “Should you need help on your thesis, please ask your supervisor.”

- “The bank is more than happy to discuss financing options should you wish to take out a loan.”

- Expressing surprise

Occasionally, should is used to emphasize surprise at an unexpected situation, outcome, or turn of events.

We do so by phrasing the surprising information as a question, using a question word like who or what and often inverting should with the subject. (However, the sentence is spoken as a statement, so we punctuate it with a period or exclamation point, rather than a question mark.)

The “question” part of the sentence is introduced by the word when, with the “answer” introduced by the word but. For example:

- “I was minding my own business, when who should I encounter but my brother Tom.”

- “The festival was going well when what should happen but the power goes out!”

Uses of should in British English.

There are a number of functions that should can perform that are more commonly used in British English than in American English. Several of these are substitutions of would, while other uses are unique unto themselves.

Should vs. would in British English

There are several modal constructions that can either take would or should. American English tends to favor the modal verb would in most cases, but, in British English, it is also common to use should, especially to add formality.

Polite advice

We can use should/would in the first person to politely offer advice about something. (It is common to add the phrase “if I were you” at the end, thus creating a conditional sentence.) For example:

- “I should/would apologize to the boss if I were you.”

- “I shouldn’t/wouldn’t worry about that right now.”

Expressing desires

We can use either should or would with the main verb like in the first person to express or inquire about a person’s desire to do something. (We can also use the main verb care for more formal or polite sentences.) For example:

- “I should/would like to go to the movies later.”

- “We shouldn’t/wouldn’t care to live in a hot climate.”

- “I should/would like a cup of tea, if you don’t mind.”

- “I don’t know that I should/would care for such an expensive house.”

Asking the reason why

In addition to asking the reason why a certain obligation or requirement is the case, we can also use should in the same way as would to ask the reason something happened or is true. For instance:

- “Why should/would my brother lie to me?”

- “Why should/would they expect you to know that?”

If we use I or we as the subject of the question, it is often used rhetorically to suggest that a question or accusation is groundless or false, as in:

- “Why should/would I try to hide anything from you?”

- “Why should/would we give up now, when we’ve come so close to succeeding?”

To show purpose

Should and would can also be used after the phrase “so that” and “in order that” to add a sense of purpose to the main verb, as in:

- “I brought a book so that I shouldn’t/wouldn’t be bored on the train ride home.”

- “He bought new boots in order that his feet should/would remain dry on the way to work.”

After other words and phrases

There are several instances in British English in which should is used after the relative pronoun that or certain other phrases to create specific meanings, especially in more formal language.

To express an opinion or feeling

When we use a noun clause beginning with that as an adjective complement, we can use should in it to express an opinion or sentiment about what is said. For example:

- “It’s very sad that she should be forced to leave her house.”

- “Isn’t it strange that we should meet each other again after all these years?”

Conditional circumstances

Similarly, should can be used after the phrases for fear (that), in case (that), and (less commonly) lest (that) to demonstrate the possible conditional circumstances that are the reason behind a certain action. For example:

- “I always pack my rain jacket when I cycle for fear (that) it should start raining midway.”

- “You should pack a toothbrush in case (that) you should be delayed at the airport overnight.”

- “She makes sure to set the alarm before leaving lest (that) someone should try to break in.”

Modal Auxiliary Verbs – Can

Definition

As a modal auxiliary verb, can is most often used to

- express a person or thing’s ability to do something. It is also used to

- express or ask for permission to do something,

- to describe the possibility that something can happen, and

- to issue requests and offers.

- Expressing ability

Can is used most often and most literally to express when a person or thing is physically, mentally, or functionally able to do something. When it is used with not to become negative, it forms a single word, cannot (contracted as can’t). For example:

- “John can run faster than anyone I know.”

- “It’s rare to find a phone that cannot connect to the Internet these days.”

- “We don’t have to stay—we can leave if you want to.”

- “Can your brother swim?”

- “I don’t think he can”

- “Just do the best you can.”

- “Can’t you just restart the computer?”

- “When can you start?”

“Can do”

In response to a request or an instruction, it is common (especially in American English) to use the idiomatic phrase “can do.” This usually stands on its own as a minor sentence. For example:

- Speaker A: “I need you to fix this tire when you have a chance.”

- Speaker B: “Can do!”

- Speaker A: “Would you mind making dinner tonight?”

- Speaker B: “Can do, darling!”

The phrase has become so prolific that it is also often used as a modifier before a noun to denote an optimistic, confident, and enthusiastic characteristic, as in:

- “His can-do spirit is infectious in the office.”

- “We’re always looking for can-do individuals who will bring great energy to our team.”

We can also make this phrase negative, but we use the word no at the beginning of the phrase rather than using the adverb not after can, as we normally would with a modal verb. For example:

- Speaker A: “Is it all right if I get a ride home with you again tonight?”

- Speaker B: “Sorry, no can do. I need to head to the airport after work.”

- Permission

We often use can to express permission* to do something, especially in questions (interrogative sentences).

For example:

- “Can I go to the bathroom, Ms. Smith?”

- “Can Jenny come to the party with us?”

- “You can leave the classroom once you are finished with the test.”

- “You can’t have any dessert until you’ve finished your dinner.”

(*Usage note: Although it is sometimes considered grammatically incorrect to use can instead of may to express permission, it is acceptable in modern English to use either one. Can is very common in informal settings; in more formal English, though, may is still the preferred modal verb.)

As a rhetorical device

Sometimes, we use can in this way as a rhetorical device to politely introduce or emphasize an opinion or sentiment about something, in which case we invert can with the subject. For instance:

- “Can I just say, this has been the most wonderful experience of my life.”

- “Can we be clear that our firm will not be involved in such a dubious a plan.”

- “And, can I add, profits are expected to stabilize within a month.”

Note that we can accomplish the same thing by using the verbs let or allow instead, as in:

- “Let me be clear: this decision is in no way a reflection on the quality of your work.”

- “Allow us to say, we were greatly impressed by your performance.”

Adding angry emphasis

Can is sometimes used to ironically or sarcastically give permission as a means of adding emphasis to an angry command, especially in conditional sentences. However, this is a very informal usage, and it is not common in everyday speech or writing. For example:

- “You can walk home if you’re going to be so ungrateful!”

- “If he continues being so insufferable, he can have his party all alone!”

- “You can just go to your room and stay there, young man! I’m sick of listening to your backtalk.”

- Possibility and likelihood

Similar to using can to express ability, we also use can to describe actions that are possible. It may appear to be nearly the same in certain cases, but the usage relates less to physical or mental ability than to the possibility or likelihood of accomplishing something or of something occurring. For instance:

- “You can get help on your papers from your teaching assistant.”

- “My mother-in-law can be a bit overbearing at times.”

- “People forget that you can get skin cancer from tanning beds.”

- “It can seem impossible to overcome the debt from student loans.”

Negative certainty and disbelief

We use the modal verb must to express certainty or high probability, but we generally use can’t (or, less commonly, cannot) to express negative certainty, extremely low likelihood, or a disbelief that something might be true. For example:

- “You can’t be tired—you’ve been sleeping all day!”

- “I can’t have left my phone at home, because I remember packing it in my bag.”

- “After three years of college, she wants to drop out? She cannot be serious.”

- Making requests

It is common to use can to make a request of someone. For example:

- “Can you get that book down from the shelf for me?”

- “Your sister is a lawyer, right? Can she give me some legal advice?”

- “Can you kids turn your music down, please?”

However, this usage can sometimes be considered too direct or forceful, and it may come across as impolite as a result. In more formal or polite circumstances, we can use other modal verbs such as could or would to create more polite constructions, as in:

- “Would you please be quiet?”

- “Could you help me with this assignment?”

- Making offers

While it might be seen as impolite to use can to make a request, it is perfectly polite to use it to make an offer. For example:

- “Can I do anything to help get dinner ready?”

- “Can I help you find what you need?”

- “Can I give you a ride home?”

If we want to be even more polite or add formality to the offer, we can use may instead, as in:

- “May I be of some assistance?”

- “May we help you in any way?”

- “How may our staff be of service to you?”

Modal Auxiliary Verbs – Could

Definition

The modal verb could is most often used as a

- past-tense version of can, indicating what someone or something was able to do in the past;

- it can also be used instead of can as a more polite way of making a request or asking for permission.

- Could is also used to express a slight or uncertain possibility, as well as to make a suggestion or offer.

- Past ability

When describing what a person or thing was physically, mentally, or functionally able to do in the past, we use could instead of can. For example:

- “When I was younger, I could run for 10 miles without breaking a sweat!”

- “Back in the 1970s, our TV could only get about four channels.”

- “She couldn’t read until she was nearly 12 years old.”

- “Could your family afford any food during the Great Depression, Grandma?”

We also use could instead of can when describing an ability that is desired or wished for. (This is known as the subjunctive mood, which is used for describing hypothetical or unreal situations.) For example:

- “I wish I could swim; it looks like so much fun.”

- Conditional sentences

Conditional sentences in the past tense are called second conditionals. Unlike the first conditional, we use the second conditional to talk about things that cannot or are unlikely to actually happen.

To create the second conditional, we usually use the past simple tense after the if clause, followed by would + a bare infinitive to describe what would be the expected (if unreal) result of the condition.

However, if we want to describe what we would be able to do under a certain condition, we can use could instead. For example:

- “If I got that promotion at work, I could finally afford a new car!”

- “If we moved to California, I could surf every day!”

We often use could in what’s known as a mixed conditional, which occurs when the tense in one part of a conditional sentence does not match the other half. This often occurs with could when a present-tense verb is being used in an if conditional clause to express a hypothetical scenario that is likely to or possibly could happen. For example:

- “If I get some money from my parents, we could go to the movies.”

- “We could visit our friends at the beach if you ask your boss for Friday off.”

- Asking for permission

When we ask someone for permission to do something, it is often considered more polite to use could instead of can. However, we can only make this substitution when asking for permission—when stating or granting permission, we can only use can (or, more politely, may).

For example:

- “Dad, could I spend the night at my friend’s house?”

- “Could we invite Sarah to come with us?”

- “I was wondering if I could take a bit of time off work.”

- Making a request

Just as we use could instead of can to be more polite when asking for permission, it is also considered more polite to substitute could when making a general request. For example:

- “Could you please be quiet?”

- “Could you help me with this assignment?”

Note that we can also do this with the modal verb would:

- “Would you ask Jeff to come over here?”

- “Would Tina help me paint this fence?”

- As a rhetorical device

Sometimes, we use could as a rhetorical device to politely introduce or emphasize an opinion or sentiment about something, in which case we invert could with the subject. For instance:

- “Could I just say, this has been a most wonderful evening.”

- “And could I clarify that I have always acted solely with the company’s interests in mind.”

- “Could I add that your time with us has been greatly appreciated.”

Note that we can accomplish the same thing by using the verbs let or allow instead, as in:

- “Let me clarify: this decision is in no way a reflection on the quality of your work.”

- “Allow me to add, we were greatly impressed by your performance.”

- Possibility and likelihood

Like can, we can also use could to describe actions or outcomes that are possible or likely. Unlike using could to talk about an ability, this usage is not restricted to the past tense. For instance:

- “I think it could rain any minute.”

- “She could be in big trouble over this.”

- “Due to this news, the company could see a sharp drop in profits next quarter.”

- “Be careful, you could hurt someone with that thing!”

- “Answer the phone! It could be your father calling.”

- Making a suggestion

Similar to expressing a possible outcome, we can also use could to suggest a possible course of action. For instance:

- “We could go out for pizza after work on Friday.”

- “You could see if your boss would let you extend your vacation.”

- “I know it will be tricky to convince your parents, but you could try.”

- Adding angry emphasis

We also use could to add emphasis to an angry or frustrated remark. For example:

- “My mother has traveled a long way to be here—you could try to look a little more pleased to see her!”

- “You could have told me that you didn’t want a party before I spent all this time and effort organizing one!”

9 .Making offers

In addition to using could to make a suggestion, we can also use it to make an offer to do something for someone. For example:

- “Could I give you a hand with dinner?”

- “Could we help you find what you need?”

- “Could I give you a ride home?”

Rhetorical questions

Could is sometimes used informally in sarcastic or rhetorical questions that highlight a behavior someone finds irritating, unacceptable, or inappropriate. It is often (but not always) used with be as a main verb. For example:

- “Could you be any louder? I can barely hear myself think!”

- “Oh my God, Dad, could you be any more embarrassing?”

- “Danny, we’re going to be late! Could you walk any slower?”

Modal Auxiliary Verbs – May

Definition

The modal verb may is used to ask, grant, or describe permission; to politely offer to do something for someone; to express the possibility of something happening or occurring; or to express a wish or desire that something will be the case in the future. We can also use may as a rhetorical device to express or introduce an opinion about something.

Asking or granting permission

May is very commonly used to express or ask for permission to do something. There are other ways to do this (by using the modals can or could, for instance), but may is considered the most polite and formally correct way to do so. For example:

- “May I borrow your pen, please?”

- “May we ask you some questions about your experience?”

- “General, you may fire when ready.”

- “She may invite one or two friends, but no more than that.”

- “May we be frank with you, Tom?”

- “Students may not leave the class once their exams are complete.”

Making a polite offer

Like can, we can use may to offer do something for someone else, though it is generally a more polite, formal way of doing so. For example:

- “May I help you set the table?”

- “May we be of assistance in any way?”

Expressing possibility

Another common use of may is to express the possibility that something will happen or occur in the near future, especially when that possibility is uncertain. For instance:

- “I’m worried that it may start raining soon.”

- “We may run into some problems down the line that we didn’t expect.”

- “I may be coming home for the winter break, depending on the cost of a plane ticket.”

- “Although we may see things improve in the future, there’s no guarantee at the moment.”

- “There may not be any issues at all; we’ll just have to see.”

Expressing wishes for the future

May is also used in more formal language to express a wish or desire that something will be the case in the future. When used in this way, may is inverted with the subject, as in:

- “May you both have a long, happy life together.”

- “May you be safe in your journey home.”

- “We’ve had great success this year; may we continue to do so for years to come.”

- “May this newfound peace remain forever between our two countries.”

As a rhetorical device

Sometimes, we use may in this way as a rhetorical device to politely introduce or emphasize an opinion or sentiment about something, in which case we invert may with the subject. For instance:

- “May I just say, this has been the most wonderful experience of my life.”

- “May we be clear that our firm will not be involved in such a dubious plan.”

- “May I be frank: this is not what I was hoping for.”

Note that we can accomplish the same thing by using the verbs let or allow instead, as in:

- “Let me be clear: this decision is in no way a reflection on the quality of your work.”

- “Allow us to say, we were greatly impressed by your performance.”

May not vs. Mayn’t (vs. Can’t)

Grammatically, it is not technically incorrect to contract may not into the single-word mayn’t. For instance:

- “You mayn’t wish to share these details with others.”

- “No, you mayn’t go to the dinner unaccompanied.”

However, this has become very rare in modern English, and generally only occurs in colloquial usage. In declarative sentences, it is much more common to use the two words separately, as in:

- “Employees may not use company computers for recreational purposes.”

- “There may not be much we can do to prevent such problems from occurring.”

It is also uncommon, though, to use may not in questions, in which may is inverted with the subject. The resulting construction (e.g., “may I not” or “may we not”) sounds overly formal in day-to-day speech and writing. Because of this, it is much more common to use the contraction can’t instead, as in:

- “Can’t we stay for a little while longer?”

- “Can’t I bring a friend along with me?”

Modal Auxiliary Verbs – Might

Definition

The modal verb might is most often used to express an unlikely or uncertain possibility. Might is also used to very formally or politely ask for permission, and it is used as the past-tense form of may when asking permission in reported speech. It can also be used to suggest an action, or to introduce two differing possibilities.

Expressing possibility

When we use might to indicate possibility, it implies a very weak certainty or likelihood that something will happen, occur, or be the case. For instance:

- “I’m hoping that she might call me later.”

- “We might go to a party later, if you want to come.”

- “You should pack an umbrella—it looks like it might”

- “There might be some dinner left over for you in the fridge.”

In conditional sentences

We also often use might to express a possibility as a hypothetical outcome in a conditional sentence. For example:

- “If we don’t arrive early enough, we might not be able to get in to the show.”

- “We still might make our flight if we leave right now!”

- “If we’re lucky, we might have a chance of reversing the damage.”

Politely asking for permission

Although may is the “standard” modal verb used to politely ask for permission, we can also use might if we want to add even more politeness or formality to the question. For example:

- “Might we go to the park this afternoon, Father?”

- “Might I ask you a few questions?”

- “I’m finished with my dinner. Might I be excused from the table?”

However, even in formal speech and writing, this construction can come across as rather old-fashioned, especially in American English. It more commonly occurs in indirect questions—i.e., declarative sentences that are worded in such a way as to express an inquiry (though these are technically not questions). For example:

- “I was hoping I might borrow the car this evening.”

- “I wonder if we might invite Samantha to come with us.”

Past tense of may

When we use reported speech, we traditionally conjugate verbs one degree into the past. When may has been used, especially to ask for permission, in a sentence that is now being reported, we use might in its place, as in:

- “He asked if he might use the car for his date tonight.”

- “She wondered if she might bring a friend to the show.”

However, this rule of conjugating into the past tense is largely falling out of use in modern English, and it is increasingly common to see verbs remain in their original tense even when being reported.

Making suggestions

Might can also be used to make polite suggestions to someone. This is much less direct and forceful than using should: it expresses a suggestion of a possible course of action rather than asserting what is correct or right to do. For example:

- “You might ask your brother about repaying that loan the next time you see him.”

- “It tastes very good, though you might add a bit more salt.”

- “You might try rebooting the computer; that should fix the problem for you.”

Suggesting a possibility

In a similar way, we can use might to suggest a possible action or situation to another person. For example:

- “I was wondering if you might be interested in seeing a play with me later.”

- “I thought you might like this book, so I bought you a copy.”

Adding angry emphasis

Just as we can with the modal verb could, we can use might to make a suggestion as a means of adding emphasis to an angry or frustrated remark. For example:

- “My mother has traveled a long way to be here—you might try to look a little more pleased to see her!”

- “You might have told me that you didn’t want a party before I spent all this time and effort organizing one!”

Introducing differing information

Another use of might is to introduce a statement that is contrary to or different from a second statement later in the sentence. This can be used as a means of highlighting two different possible outcomes, scenarios, or courses of action. For example:

- “Sure, you might be able to make money quickly like that, but you’re inevitably going to run into difficulties down the line.”

- “I might not have much free time, but I find great satisfaction in my work.”

- “Our organization might be very small, but we provide a unique, tailored service to our clientele.”

As a rhetorical device

Sometimes, we use might as a rhetorical device to politely introduce or emphasize an opinion or sentiment about something, in which case we invert might with the subject. For instance:

- “Might I just say, this has been a most wonderful evening.”

- “And might I clarify that I have always acted solely with the company’s interests in mind.”

- “Might I add that your time with us has been greatly appreciated.”

Note that we can accomplish the same thing by using the verbs let or allow instead, as in:

- “Let me clarify: this decision is in no way a reflection on the quality of your work.”

- “Allow me to add, we were greatly impressed by your performance.”

Modal Auxiliary Verbs – Must

Definition

The modal verb must is most often used to express necessity—i.e., that something has to happen or be the case. We also use this sense of the word to indicate a strong intention to do something in the future, to emphasize something positive that we believe someone should do, and to rhetorically introduce or emphasize an opinion or sentiment. In addition to indicating necessity, must can be used to indicate that something is certain or very likely to happen or be true.

Necessity

When must indicates that an action, circumstance, or situation is necessary, we usually use it in a declarative sentence. For example:

- “This door must be left shut at all times!”

- “We absolutely must get approval for that funding.”

- “You must not tell anyone about what we saw.”

- “Now, you mustn’t be alarmed, but we’ve had a bit of an accident in here.”

We can also use must in interrogative sentences to inquire whether something is necessary, usually as a criticism of some objectionable or undesirable action or behavior. For instance:

- “Must we go to dinner with them? They are dreadfully boring.”

- “Must you be so rude to my parents?”

- “Must I spend my entire weekend studying?”

However, this usage is generally reserved for more formal speech and writing, and isn’t very common in everyday English.

Indicating strong intention

We use the same meaning of must to indicate something we have a very strong intention of doing in the future. For example:

- “I must file my taxes this weekend.”

- “I must get around to calling my brother.”

- “We must have the car checked out soon.”

Emphasizing a suggestion

We also use this meaning to make suggestions to others of something positive we believe they should do, as in:

- “You simply must try the new Ethiopian restaurant on 4th Avenue—it’s fantastic!”

- “It was so lovely to see you. We must get together again soon!”

- “You must come stay with us at the lake sometime.”

As a rhetorical device

Finally, we can also use this meaning of must as a rhetorical device to politely introduce or emphasize an opinion or sentiment about something:

- “I must say, this has been a most wonderful evening.”

- “And I must add that Mr. Jones has been an absolute delight to work with.”

- “I must be clear: we will disavow any knowledge of this incident.”

Note that we can accomplish the same thing by using the verbs let or allow instead, as in:

- “Let me be clear: this decision is in no way a reflection on the quality of your work.”

- “Allow us to say, we were greatly impressed by your performance.”

Certainty and likelihood

In addition to being used to indicate a necessary action or situation, must is also often used to describe that which is certain or extremely likely or probable to happen, occur, or be the case. For example:

- “You must be absolutely exhausted after your flight.”

- “Surely they must know that we can’t pay the money back yet.”

- “There must be some way we can convince the board of directors.”

- “I must have left my keys on my desk at work.”

- Speaker A: “I just got back from a 12-week trip around Europe.”

- Speaker B: “Wow, that must have been an amazing experience!”

Generally speaking, we do not use the negative of must (must not or mustn’t) to express a negative certainty or strong disbelief. Instead, we use cannot (often contracted as can’t), as in:

- “You can’t be tired—you’ve been sleeping all day!”

- “I can’t have left my phone at home, because I remember packing it in my bag.”

- “After three years of college, she wants to drop out? She cannot be”